Blue stars pulsating in the night

In the middle of the large Chilean Atacama desert, a team of Polish astronomers monitors millions of celestial bodies night after night with the help of a modern robotic telescope. In 2013, the team was surprised when they discovered, in the course of their survey, stars that varied much faster than expected. In the following years, the team including Dr. Marilyn Latour, an astronomer from the Dr. Remeis-Sternwarte Bamberg, the astronomical institute of the Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nuremberg, studied the stars in more detail and concluded that they had discovered a new class of variable star. Their results have been recently published in Nature Astronomy.

FAU-astronomer discovers new class of variable dwarf star

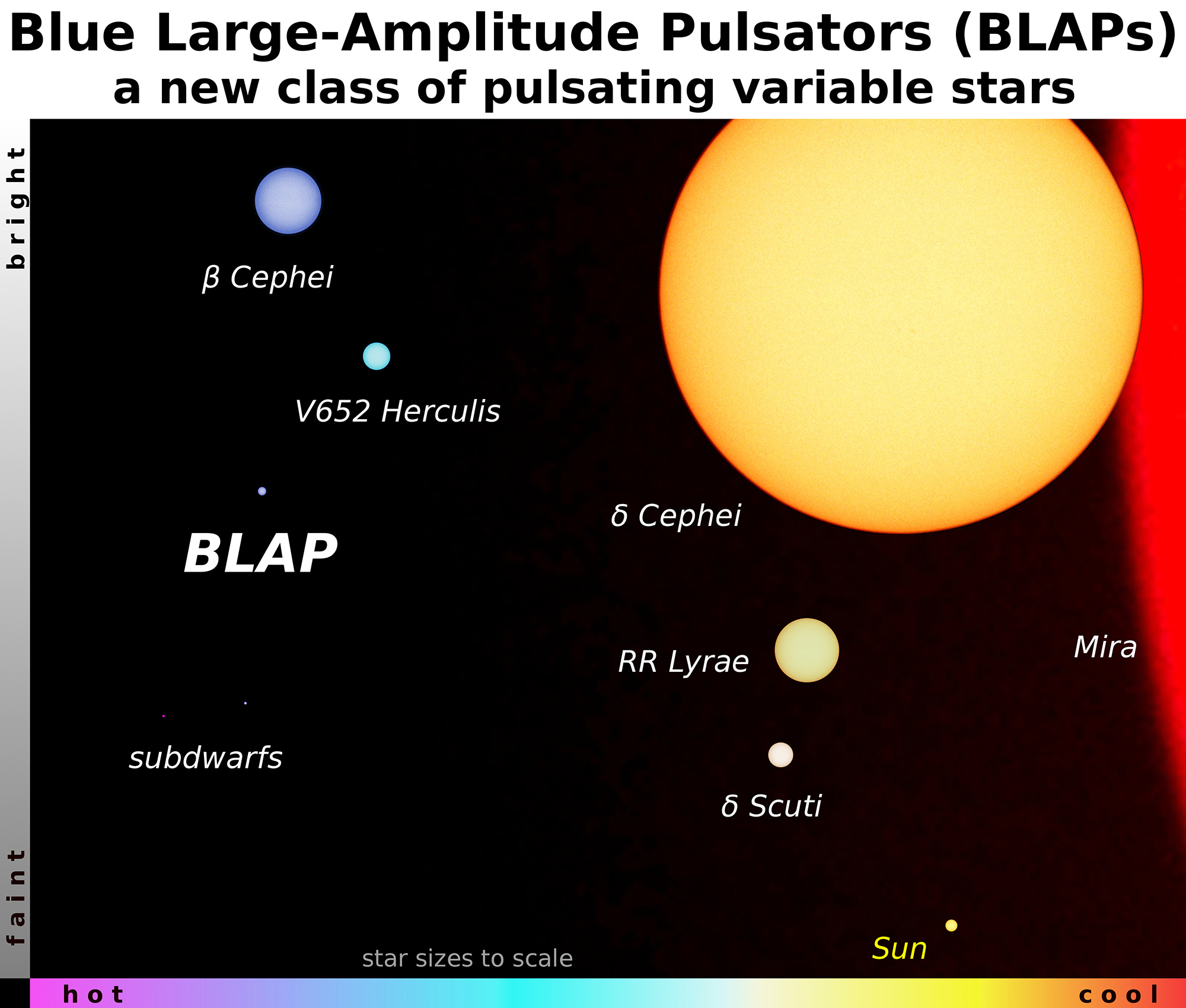

Many classes of star show brightness variations. Unlike our Sun, these stars are not stable; their surface oscillates, meaning that the surface expands and shrinks by a few percent. This is the case for the well-known Cepheids and RR Lyrae stars, which show oscillation periods ranging from a few hours to hundreds of days.

The researchers discovered a dozen of stars that seemed at first glance to vary in a very similar way to the Cepheids and RR Lyrae stars, but with much shorter (20-40 minutes) oscillation periods and their colour is much bluer. This indicates that the newly discovered stars are hotter and more compact. These properties were the motivation for the proposed acronym of the new class of variable stars: BLAPs – Blue Large-Amplitude Pulsators. The nature of these stars, however, remained a matter of speculation.

The nature of the newly discovered stars

The nature of the stars posted the researchers a riddle. At first, the astronomers assumed that BLAPs could be hot dwarf stars since they have similar oscillation periods. Hot dwarf stars are old stars approaching the end of their lives. They generate their energy via the thermonuclear fusion of helium into carbon. The Sun, being in an earlier phase of its life, is currently burning hydrogen into helium.

In order to find out whether BLAPs are actually hot dwarfs the researchers made observations with two of the largest telescopes. The astronomers were able to secure suitable spectra of some BLAPs using the large Gemini and Magellan telescopes, both located in the Chilean Atacama desert. Dr. Latour analyzed those spectra using sophisticated physical-numerical models. She showed that the light variations are due to temperature changes at the surface of the star. The temperature of the BLAPs turned out to be five time larger than that of the Sun, which is typical for hot dwarfs.

However, the BLAPs are significantly bigger than hot dwarfs, meaning that they form a new class of stars similar to hot dwarfs but with bloated envelopes. Why BLAPs oscillate like Cepheids and why they are bloated remains a puzzle, as well as their formation history. The mystery of the origin of the BLAPs needs to be solved by new investigations.